Lights flashed and a recorded siren blared as a small group of medical students kneeled around a mannequin. Two applied tourniquets to the mannequin’s severed leg and wrist, while a third pressed gauze into an open wound and a fourth checked for other injuries.

After two and a half minutes, the students’ time was up.

The instructor, army combat medic and third-year medical student Jason Hasegawa, pointed out injuries they missed. “This is how you get tunnel vision,” he explained while gesturing at the amputated leg.

In a neighboring room, another instructor chastised a second group of students who made the opposite error. “His arm was off, and you guys addressed that last. Priorities, right? You want to address the biggest source of bleeding first.”

The simulations, presented in conjunction with a nationwide training course called Stop the Bleed, weren’t a random set of injuries. Each scenario was based on a call Hasegawa has experienced as a first responder, emergency medical technician, and, more recently, as a medic and second lieutenant in the U.S. Army.

His goal in helping teach this course, along with a tactical medicine course he taught in fall 2021, was to help prepare doctors to care for patients in uncontrolled environments. “I always felt there was a gap between clinicians and first responders, and I want to bridge that gap,” he said.

The popularity of his first tactical medicine course inspired second-year medical students Haad Arif and Kayhon Rabbani to work with Hasegawa to co-found a new student interest group, the Disaster Medicine Interest Group (DMIG), ensuring that training continues as Hasegawa approaches the end of his time at the UC Riverside School of Medicine. The group aims to teach students to deliver high-quality emergency medical care and disaster relief in a range of environments and under pressure.

“DMIG is unique because the students are looking for more than the typical lectures,” said Nicholas Sheets, MD, the group’s faculty advisor and a trauma surgeon at Riverside Community Hospital. “Disaster medicine is becoming more relevant, as we can see in the news. It is a multidisciplinary field that spans from prevention to community outreach, such as Stop the Bleed courses, to first responders, to triage and medical management.”

Beyond its uses for emergency medical technicians and military service members, disaster medicine training teaches a range of skills applicable to everyday situations. “DMIG specifically focuses on training for the austere environment, whether that be in the wilderness, active shooter environments, or even just resource constrained environments in underserved communities like the Inland Empire,” said Hasegawa. “How do we make tourniquets, or how do we treat a gunshot wound in the field, and not a well-lit environment?” he added. “It has everything to do with being a physician because we’re not always in the hospital. Sometimes we’re off duty.”

When needed, though, he said the mindset carries over into hospitals too. “If I had to take a guess, the kind of people that leave this program at UCR are the same kind of individuals that would continue working in underserved communities where they don’t always have all the equipment they need,” Hasegawa said. “If we don’t have the resources that we would like to have—that's fine. We’re constantly thinking and adapting on the fly.”

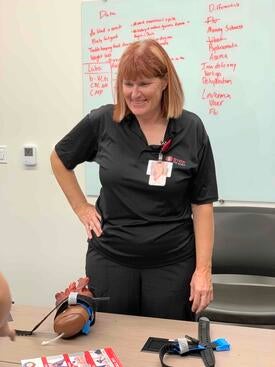

The Stop the Bleed course exemplifies the types of training the group offers. In addition to the timed simulations, students practiced using tourniquets at a third station and attended a classroom presentation led by Wendy McEuen, a nurse at Riverside Community Hospital.

“Anything you’ve seen on Grey’s Anatomy, I’ve probably seen it in the ER,” she told the assembled medical students before launching into the training’s fundamental steps, known as the ABC’s of bleeding: Alert emergency personnel, locate the Bleeding, and Compress to stop the bleeding.

After five years of teaching Stop the Bleed courses in the area to help people of all ages learn to respond to injuries, McEuen said the training helps make the community better as a whole. “I feel like it empowers people to do something, whereas before they might be intimidated by trying to help,” she explained. “If they at least attempt something, then the person has a better chance of survival.”

It’s also essential hands-on practice for medical students. The training at UCR takes advantage of the school’s state-of-the-art Center for Simulated Patient Care to give students realistic experiences on lifelike mannequins that can talk, provide feedback on various medical procedures, and even bleed.

“Even some residents that come to the hospital may have never used a tourniquet,” said McEuen. “They may have been taught the basics, but they may have never had the application part of it.” She noted the value of developing muscle memory, which students practice in the simulation portions of the course.

Rabbani and Arif also stressed the importance of practice.

“Even if you know what to do and how to do it, prioritizing what’s important, in what order it is to save their life most effectively, is another skill that [students] learn here,” said Rabbani, who serves as the group’s co-chair with Arif. “Pretty much everything in medicine you can look up on YouTube or on the internet, but knowing exactly the order of which things should be done and being able to have a hands-on scenario to practice is unique to what we do here in the Sim Lab.”

With this training, Arif added, third- and fourth-year medical students entering their clerkships have more exposure, confidence, and skills to care for their patients.

As Hasegawa takes a more hands-off role as he approaches the end of medical school and returns to the military, Rabbani and Arif are planning to hold more classes and even train local law enforcement in disaster medicine. Still, Hasegawa believes in the group’s mission and plans to remain involved.

“It breaks my heart, all of the things you hear in the news, all the disasters and active shootings,” Hasegawa said. “I think that what we're doing here is relevant, and I think that if we can continue training our soon-to-be physicians how to respond to these disasters, if and when they occur, I think our community and our country will be better for it.”