In early March, researchers from UC Riverside visited Washington, DC, with an important message: If the United States loses its position as a global leader in science, other nations will take its place--and may withhold new discoveries impacting public health, security, and other vital areas.

The visit, led by Scott D. Pegan, PhD, associate dean of Pre-Clerkship Medical Education at the UCR School of Medicine and a U.S. Army reserve lieutenant colonel, came in response to recent cuts to National Institutes of Health (NIH) research funding as well as federal communications restrictions that threaten ongoing research projects. NIH grants provide essential support for research at the SOM and other universities throughout the nation through both direct funding of specific research projects and funding for indirect costs, essentially overhead expenses necessary for conducting research. The second category is the area the administration is targeting for cuts.

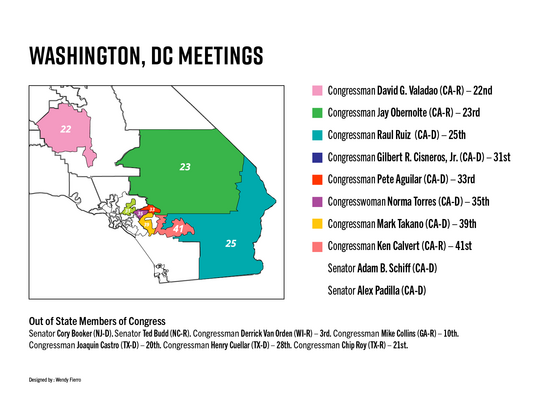

“Members of Congress and their staff do a lot of research, but sometimes they miss some of the real impact that’ll have on their constituencies,” said Pegan of his visit, which included meetings with Sen. Adam B. Schiff, Sen. Mike Collins, Rep. Mark Takano, Rep. Norma Torres, Rep. Jay Obernolte, Rep. Gilbert Cisneros (pictured above) and 11 other representatives.

Pegan said several potential consequences resonated with Congress members, including the potential for scientists to leave the U.S. for China and other nations, taking future discoveries with them. “That really puts us on a trajectory that within the next few years, if there was a need for a new medical countermeasure… that technology would no longer be controlled or produced by the United States,” he added. “That message was received very well across all members that we talked to.”

“Our elected officials really strive to make our lives better, but sometimes changes that look good on paper don’t really pan out that well,” Pegan continued, adding that the cuts may seem minor but would have three to four times the anticipated losses, inhibiting research that supports public health and security. “Most congressional members are very happy to discuss with their constituents and the public about these kinds of issues so that they can be better informed and guide their policies.”

University research serves the nation

NIH funding cuts significantly impact a variety of research at universities, including at the UCR SOM, that both safeguards and promotes public health and national security. “A lot of different parts of the federal government, including the Department of Defense, rely on the NIH to spend those dollars so that they can further develop research that comes out of that,” Pegan explained. “So it's not just public health… these cuts will also hurt national defense, because our armed forces also rely on this technology to have capabilities to go places and do things that we ask them to do.”

SOM research tracks virus development and seeks treatments for viruses that endanger U.S. troops

Pegan conducts research with implications for both national health and security. His lab is focused on finding treatments for Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus, which has proven fatal for U.S. service members abroad and may be a bioterrorism risk. “There are no therapeutics for this,” said Pegan. “That means that our armed forces that are going into these endemic areas are vulnerable… and that will hurt U.S. capabilities to respond to certain regions.”

Pegan’s lab discovered a vaccine that can provide full protection from the virus within three days after receiving one dose, and is working on additional therapeutics in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the University of Maryland, and the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID). However, funding cuts may delay their development.

In addition, Pegan’s lab is developing biosurveillance tools to track viruses as they evolve toward passing from animals to humans. The idea is to use limited national resources more effectively to focus on viruses most at risk of becoming a threat to contain them early. “It’s much better to find it, identify it early, understand the threat to national security, and then deal with it,” said Pegan.

SOM research improves public health conditions including autism, IBD, concussions, and Alzheimer’s disease

Other UCR SOM research also focuses on national public health needs.

Iryna Ethell, PhD, associate dean of Academic Affairs and a biomedical sciences professor, studies diseases that impact brain development, including autism, which affects one in 36 children in the United States. “We're identifying genes involved [with autism], environmental factors, and how we can help to alleviate some of the signs associated with autism, for example sensory sensitivity, anxiety, obsessive compulsive behavior, and cognitive inflexibility,” Ethell said.

Biomedical sciences professor Declan McCole, PhD, also researches a common condition: inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which affects up to 3.1 million U.S. adults. As environmental factors and socioeconomic conditions can also play a role in triggering the disease, his research is particularly relevant to the Inland Empire, where these detrimental factors are common.

“I have several NIH grants studying various aspects of inflammatory bowel disease, including the role of genetic risk variants and how they affect the ability of the intestine to act as a barrier to microbes,” McCole said. This includes using a gene-editing technique to correct a genetic variant then study its impact on intestinal barrier function using patients’ cells. “We think these will be really powerful tools that we can use to better understand the development of IBD and how we can develop specific treatments targeted to individual patients,” McCole said.

Research by biomedical sciences professor Andre Obenaus, PhD, serves as another example of NIH-funded projects at the SOM with broad implications for public health. His lab examines the ways that traumatic brain injury (TBI) and single or repeated concussions modify blood vessels in the brain, with the goal of finding ways to repair the vessels. A second aspect of his research investigates changes in brain vessels from Alzheimer’s disease, including modified blood flow and vessel repair mechanisms.

His research has the potential to help nearly anyone. TBIs can affect everyone from student athletes to war veterans. Alzheimer’s, the fifth leading cause of death among adults over 65 in 2021, can also impact any older adult without warning, with almost 7 million Americans having a diagnosis. However, there are no known treatments for either condition.

“Continued funding is really important to understand the pathophysiology of these disease states, and the only way we can design new treatments to alleviate them is to have a better understanding of what the cellular and molecular changes are in the brain that might lead to these perturbations,” said Obenaus.

Even seemingly minor funding cuts may decimate research

Pegan emphasized in DC that the proposed NIH funding cuts to indirect costs may seem small, but would significantly impact research and the people the research aims to serve.

“One of the big misconceptions is that the cuts are just 30% to 15%, and that's not the case,” Pegan explained. “The losses will be about three to four times that, because almost all research universities rely on those funding rates at about 50% or greater to support the infrastructure that the federal government requires to do the research.”

Funds support necessary biosecurity infrastructure

Federal regulations, which federal funding supports, require measures like biosecurity infrastructure to prevent researchers from inadvertently creating a new virus or causing other health hazards, thereby safeguarding the public. “Now you'd be taking the money away and still being told to implement that infrastructure,” Pegan said. Without the funding, he continued, UCR and other universities will be forced to reassess whether they can afford to continue the research. “The money has to come from somewhere, because you can't get away with doing research without that kind of bio-safety infrastructure,” Pegan said. “It's hard to fully predict what the implications are if these cuts go into effect, but there'd be types of research that wouldn't be able to be performed anymore in numerous locations.”

Funds provide jobs and drive economic activity

Funding cuts would also result in job losses in labs, with economic consequences. “Each NIH dollar that's spent equals $2.50 in economic activity,” Pegan said, adding that cuts would result in hundreds of millions of dollars in losses to the region. “It means not just losing the next generation of scientists, but all the support staff that are required to be trained to be able to conduct this kind of research.”

Ethell voiced a similar concern. In addition to losing jobs in the underserved, economically disadvantaged area of the Inland Empire, she explained that it takes time to train staff in the specific techniques her lab uses. However, funding uncertainties and cuts, even if only short term, could force staff to seek employment elsewhere. “Once we lose the people we train, the process of hiring and training new people may take years, so even a few months' disruption can set us back years and delay new discoveries,” Ethell said.

Funds help keep researchers, and their discoveries, in the United States

McCole added that fewer lab jobs will result in a lack of research opportunities for students. In addition, he said, loss of research funding may lead researchers to leave their universities and even the country–potentially to competing nations like China. “It has very broad negative impacts, but also local negative impacts,” he said. “We just need to try and convince the powers that be that… [research funding] is one of the best investments that the government makes.”

“Science is very flexible; it's without borders,” Ethell said. “If there's less money to do science in the U.S., researchers will go to Europe or Asia, to China… and the discoveries they'll make will stay in that country,” she continued. “If you don't fund innovative and high impact research, there will be no scientific advancements in the U.S.”

Funds support equipment sharing and cybersecurity

Ethell also pointed out that funding cuts could lead to higher research costs long term. Currently, labs share certain expensive pieces of equipment, but losing funding could derail the centralized structure that organizes the collaborations. If labs can’t share equipment, Ethell said, they’ll need to buy their own, resulting in higher costs up front but also in the future for maintenance. “Some things should be centralized, but who pays for that?” she said. “[Funding for] indirect costs is exactly covering those costs and expenses that helps not just one lab, one research project, but many different ones.”

Support infrastructure is also important for cybersecurity, according to McCole. “Without funds to support employing specialized individuals who are trained in cyber technology and can keep our information technology infrastructure safe, then we're either at risk of having research stolen, or we're at risk of ransomware, which is a major concern for academic institutions,” he said.

Funds let researchers continue to seek new treatments for affected communities

Obenaus focused on the need for funding to find treatments and help the many people affected by Alzheimer’s disease, traumatic brain injuries, and other health conditions.

“We know Alzheimer's is going to be one of the fastest-growing disease states in the United States over the next 20, 25 years, and cutting funding on a broad scale would certainly impact our progress in understanding these disease states,” he said.

This would affect more than just people with Alzheimer’s and other diseases. “One of the things that's not really well discussed is these cuts may delay research, but that also impacts caregivers and the economics of the region,” Obenaus said.

He added that the cuts would produce a domino effect. “Let's say in five years, I come up with a drug under the current schema that could help Alzheimer's disease,” he said. “But let's say that my funding gets cut, and it takes another 10 years instead of five to get that drug out the door; that certainly has socioeconomic impacts long beyond what those cuts would be.”

“There's no good upside to these cuts,” he continued. “Research is a cumulative effort. When everybody's pulling the wagon in the same direction, that'll make the difference. And if you have these cuts, you really are delaying the subsequent goal of research to improve human lives.”

Obenaus added that the solution isn’t as simple as having commercial companies take over treatment development instead. He explained that researchers focus on understanding disease states, while for-profit enterprises focus on developing drugs most efficiently. “Those are not necessarily exclusive to each other,” Obenaus said, “but they certainly can diverge at some point where they are not seeking the same goal.”

Eyes on the future

Pegan emphasized that his recent DC trip is only part of ongoing efforts to bring awareness to the importance of research funding and other issues.

“These kinds of trips aren’t about changing a person’s mind,” he said. “These conversations are more about sharing information to help our lawmakers understand the impact of policies on the ground…so when lawmakers seek to make decisions, they have the best information available to them.”

He framed the trip as a success. “I think we achieved what we hoped to do in terms of bringing awareness to the several usually unseen downstream aspects of what's going on in terms of research support from the federal government,” Pegan said, particularly in bringing attention to potential biosecurity threats and the possibility of competing nations overtaking the U.S. in research.

He added that ongoing communication is necessary to convey the importance of research. “A lot of times the public just hear that, ‘Oh, we're cutting science, that doesn't really mean anything to me, because that's some person studying something that doesn't apply to me,’” Pegan said, explaining that the issue may stem from ineffective communication from scientists. “We’re so in the weeds trying to make the science go that sometimes we fall short on directly engaging the public who we are all trying to serve.”

Just as U.S. research is resuming after slowdowns and shifts in focus during the pandemic, Pegan added, the cuts will once again set it back. “They will put us on a trajectory where we'll not be the leader in science in the coming decades,” Pegan said. “And if you're not the leader, you're a follower.”